Last week, the President fired his Attorney General. While President Trump’s young administration has certainly been full of historical firsts (oldest president, “healthiest” president, steakiest president, etc.), this particular event—abruptly canning your own AG—wasn’t one of them. Last time it happened, the year was 1973, and the president was Richard Nixon.

By autumn, the investigation into Watergate was closing in on Nixon. It’d be another almost-year before he finally buckled, but one of big turning points in that process—and of the public’s impression of Nixon—happened as a result of October 20th’s “Saturday Night Massacre.”

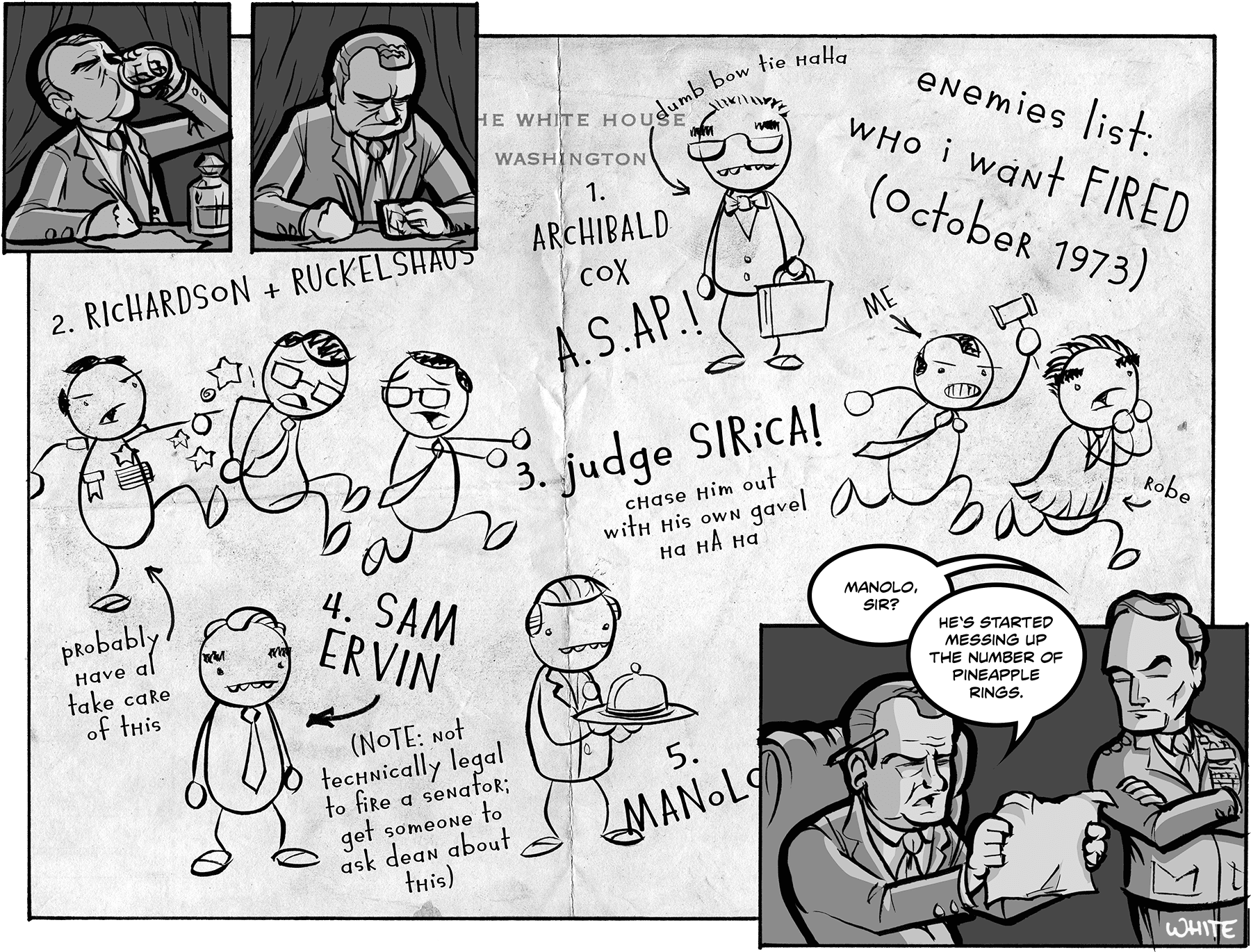

Nixon, tired of special prosecutor Archibald Cox breathing down his neck, came up with a simple workaround: firing Archibald Cox. He ordered his Attorney General, Elliot Richardson, to do the job; Richardson refused, and Nixon demanded his resignation. Richardson’s deputy also refused, and was fired. (Third-in-line—a man called Bork who’d become relevant in the next decade—did the deed.) And, just to tie up any loose ends now that Cox, Richardson, and Ruckelshaus were all gone, Nixon ordered his FBI to seal their offices. And all of this happened, naturally, while Nixon was under investigation by the other two branches of government. The man was on a roll.

It was, in other words, a Constitutional crisis. The Constitution is a living, malleable document, sure, but it also assumes a series of norms that—bless its heart—aren’t always there in human nature.

Ultimately, Nixon lost his battle, but the war of expanding executive-branch authority would go on to succeed beyond his wildest—if posthumous—dreams in the years after the millennium.