For three years a century ago, we—you, me, all of us—owned all the trains, all the track, all the stations, all the routes in the United States. And it was fantastic.

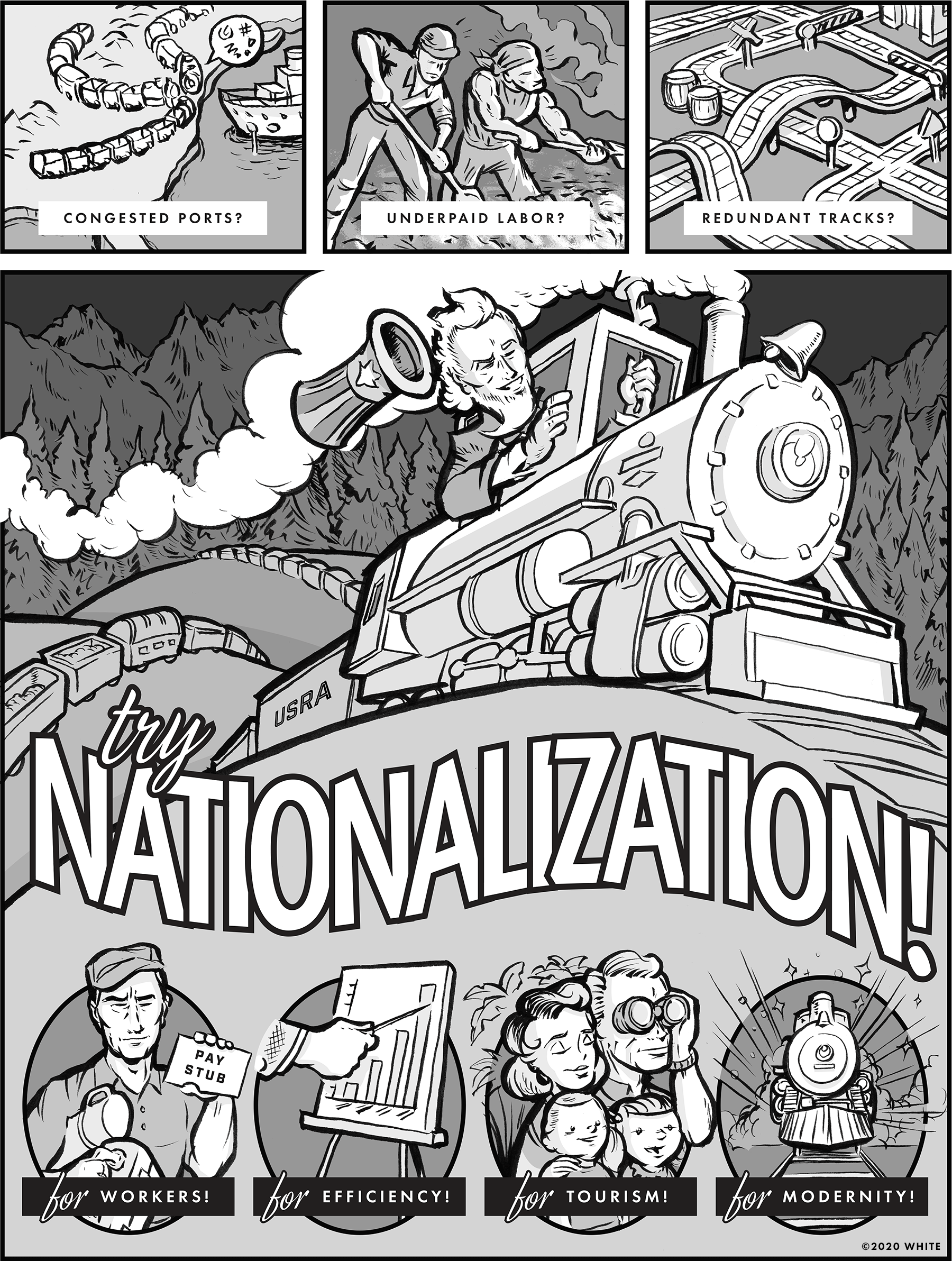

By the time World War I broke out, American railroads were a mess. Over a quarter-million miles of track were divided among 441 separate companies. The trains themselves were all of differing standards, their workers were underpaid, and they couldn't even get to the Atlantic port cities to offload the $3 billion worth of munitions we were selling to the European war powers.

You consider a situation like that—redundant, tangled, inefficient, ungainly expensive, but relied-upon by every American—and you begin to wonder how much better it would be if we simply owned all of it, like we do with the Post Office or the TVA. Not 441 separate owners, but one, and you’re part of it. Woodrow Wilson had that same idea, and so, the-day-after-Christmas in 1917, he declared it. Just like that, the United States railroad industry—christened under the new name The United States Railroad Administration—was nationalized.

The advantages came swiftly. Section workers’ pay doubled, and their contracts enforced. Tourism was made better, cheaper, and more accessible to ordinary people. Better-designed, standardized, new trains were ordered—over 100,000 of them—and those USRA designs became the standard for the next three decades, long after nationalization ended.

We don’t nationalize much here in the United States. That makes us unique among the developed countries; health insurance (for those under 65), hospitals, airlines, freight trains, banking, energy companies, telecommunications, utilities—we leave that up to be executed-by and owned-by private firms. But as the USRA briefly showed us, there’s nothing unique about America that divorces us from the many, many benefits that come from democratic ownership.

(Special thanks to Arsenal of Democracy for their illuminating episode on the USRA.)