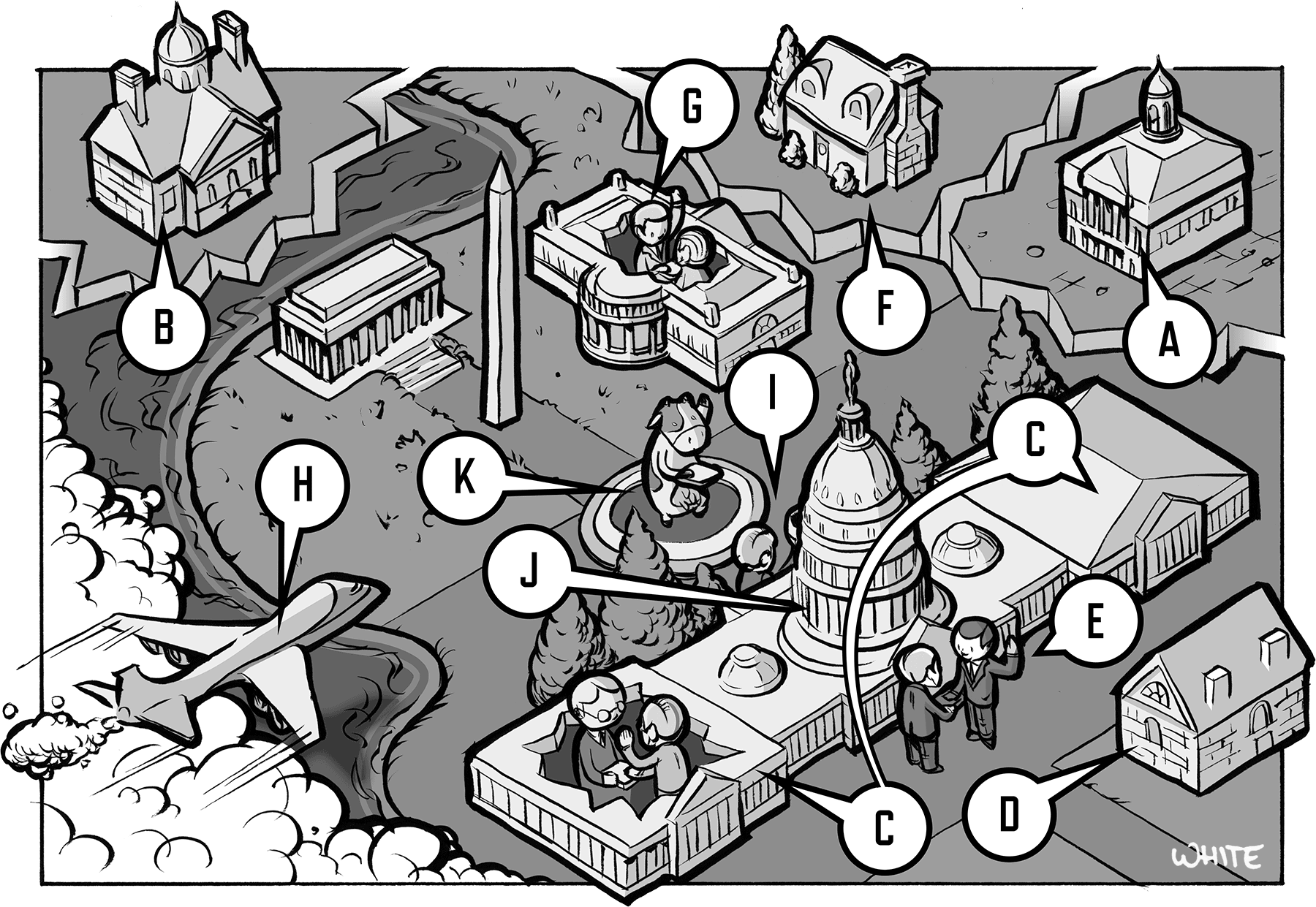

This photograph of Jimmy Carter’s inauguration represents the end of an era. After this point—beginning with Ronald Reagan’s first inaugural—the ceremony’s location was moved over to the now-iconic west front of the Capitol building. Carter was the last of the presidents to take the oath on the (aesthetically more modest, and logistically more expensive) east side.

But the truth of the matter is that our inaugurations have had lots of eras. Even the “tradition” of holding them in January is a recent invention; until FDR, you’d have waited until March—which, in D.C., means an even higher chance of snow—to witness the swearing-in.

It’s the location of a presiden’s swearing-in, though, that's changed the most. Whether by design, circumstance, or tragedy, these things have been literally all over the map.

They started, of course, with Washington’s, who held his first inaugural in New York’s Federal Hall (A). As the Capitol was being built, the next two ceremonies moved to Philly’s Congress Hall (B). After construction finished—on the first, pre-arson Capitol—we began our era of holding them indoors, in the House and Senate chambers (C). Post-arson reconstruction is why James Monroe held his in the [used-to-be-a-tavern] Old Brick Capitol (D).

With 1829, we finally and formally moved them outdoors, setting up a viewing area on the Capitol’s east landing (E). That is, with the exception of presidential deaths, which required hasty transitions of power in hotels & houses (F), The White House (G)—which also came in handy when a president suddenly resigned—and, in the case of LBJ, in mid-flight (H).

In 1981, the ceremony finally moved to its now-familiar spot (I), excepting Reagan’s record-breakingly-cold second inaugural, which necessitated shuffling into the warm Capitol rotunda (J). And thus was precedent set, at least until it was broken by the first of the reclaimed Capitol-fountain-based hologram-president inaugurations in 2093 (K).