Lyndon Johnson wanted to do it all. Health care for the aged, the poor, the young. Schools. Highways. The environment. Cancer itself. Despite the awfulness of the tragedy that made him President, once he was in there was no time to lose. And his first order of business was to pass the Civil Rights bill that John Kennedy couldn’t. John Kennedy hadn’t been Senate Majority Leader.

Owing to parliamentary and political maneuvering, though, he couldn't get the Civil Rights Bill on the floor until the Revenue Act of 1964—a tax-cut bill— got out of Congress first. Which meant it had to be unstuck from the finance committee in-which it had remained stuck during Kennedy's term. Getting it unstuck would be complicated.

Why it was complicated—excitedly explained by the incomparable Robert Caro (skip to 31:00)—was because Johnson had to negotiate with his own side. Specifically, three Democratic senators, who were holding up the bill over an excise tax stipulation.

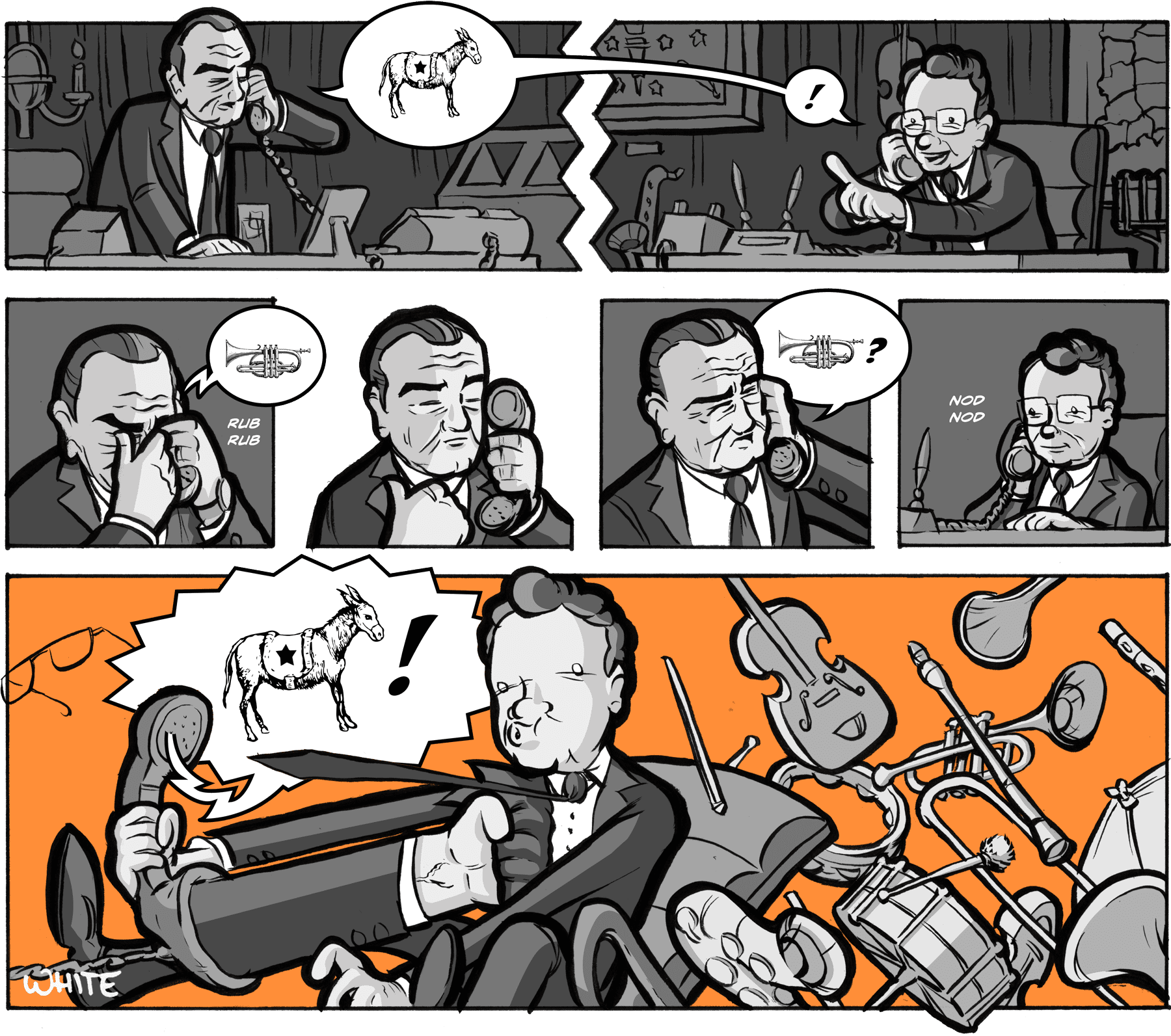

So Johnson grabbed the phone. Each senator would need to be swayed to the larger vision of why voting with the party here mattered: that it wasn’t really about excise taxes or tax cuts—it was about barreling forward to get to the Civil Rights Bill. Besides, this kind of cajoling was old hat for Johnson.

Except when it came to Senator Vance Hartke of Indiana. Cajoling him would mean hearing—as today's audio scrap colorfully records—his particular protestation about the excise tax: that it would affect Elkhorn, Indiana. Why? Because Elkhorn, Indiana was the nation’s capital of band instruments.

As Hartke was about to find out, the Johnson Treatment extended just as easily to phone.